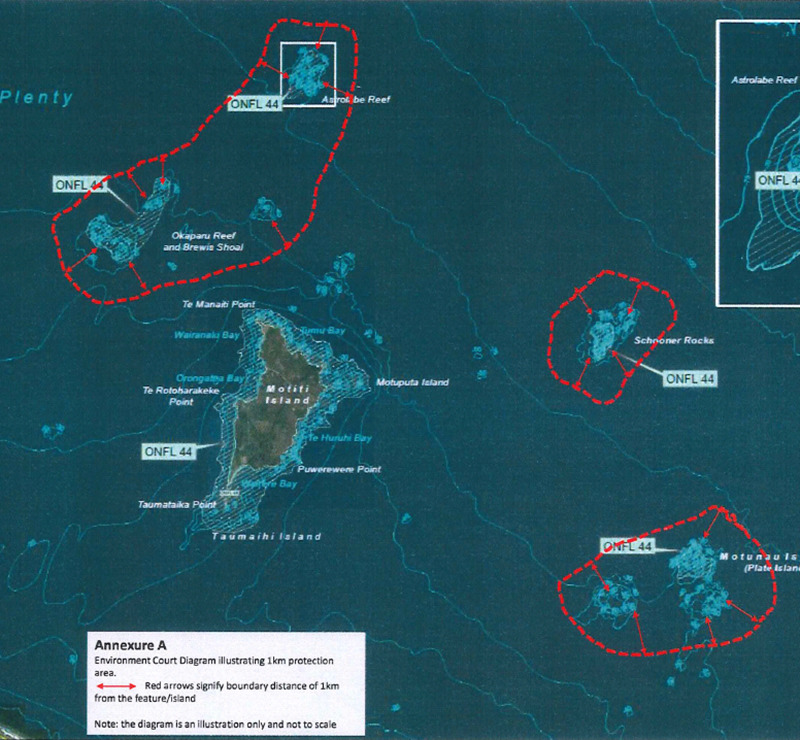

Protected areas around Motiti Island as set out in the Environment Court’s interim decision, Motiti Rohe Moana Trust v Bay of Plenty Regional Council [2018] NZEnvC 067

On 4 November 2019 the Court of Appeal concluded in a controversial decision that regional councils can use the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) to control fishing in the coastal marine area.

Back in 2015, Bay of Plenty Regional Council (BOPRC) released decisions on its Regional Coastal Environment Plan (the Plan). The area subject to the Plan included the immediate surroundings to Motiti Island, offshore Tokau Reefs and the Astrolabe Reef/Ōtāiti. This Plan was appealed to the Environment Court and it was during that process that the concept of marine protection areas came about.

The case eventually got to the Court of Appeal, in which the Court had to evaluate the jurisdictional overlap between the RMA and the Fisheries Act 1996 (Fisheries Act).

RMA and fishing

By way of background, the RMA includes the following key provisions, which are referenced throughout this article:

30 Functions of regional councils under this Act

1) Every regional council shall have the following functions for the purpose of giving effect to this Act in its region:

…

d. in respect of any coastal marine area in the region, the control (in conjunction with the Minister of Conservation) of –

i. land and associated natural and physical resources:

ii. the occupation of space in, and the extraction of sand, shingle, shell, or other natural material from, the coastal marine area, to the extent that it is within the common marine and coastal area:

…

vii. activities in relation to the surface of water:

…

ga. the establishment, implementation, and review of objectives, policies, and methods for maintaining indigenous biological diversity:

…

2) A regional council and the Minister of Conservation must not perform the functions specified in subsection (1)(d)(i), (ii) and (vii) to control the taking, allocation or enhancement of fisheries resources for the purpose of managing fishing or fisheries resources controlled under the Fisheries Act 1996.

Environment Court

Trustees of the Motiti Rohe Moana Trust v Bay of Plenty Regional Council [2016] NZEnvC 240

The Environment Court concluded that s 30(1)(ga) of the RMA – which gives regional councils functions around maintaining indigenous biological diversity – is not caught by the limitation in s 30(2) of the RMA (the Limitation). The Limitation prohibits regional councils, in exercising functions under ss 30(1)(d)(i), (ii) and (vii), from controlling the taking, allocation, or enhancement of fisheries resources for the purpose of managing fishing or fisheries resources controlled under the Fisheries Act.

High Court

Attorney-General v Trustees of the Motiti Rohe Moana Trust [2017] NZHC 1429

Attorney-General v Trustees of the Motiti Rohe Moana Trust [2017] NZHC 1886

The Attorney-General appealed this decision to the High Court. The High Court held that regional councils are precluded by the Limitation from exercising functions under ss 30(1)(d)(i), (ii) and (vii) to manage the utilisation of fisheries resources or the effects of fishing on the biological sustainability of the aquatic environment as a resource for fishing. It also concluded that regional councils can exercise their functions to maintain indigenous biological diversity under s 30(1)(ga) however only to the extent that it is “strictly necessary” to perform that function.

The High Court set aside the declarations made by the Environment Court but did not make its own declarations because it considered that answering the broad, essentially hypothetical questions posed would run the risk of overreach or oversimplification. The Attorney-General appealed this decision to the Court of Appeal.

Interim judgement of the Environment Court

Motiti Rohe Moana Trust v Bay of Plenty Regional Council [2018] NZEnvC 067

In the meantime, the Environment Court released an interim judgement declaring that a rule prohibiting the damage, destruction or removal of flora and fauna within three protection areas around Motiti Island – Ōtāiti, Motunau Island and Motuhaka – should be included in the Plan. However, the Environment Court stated that its judgement was subject to the Court of Appeal decision on jurisdiction.

Court of Appeal

Attorney-General v Trustees of the Motiti Rohe Moana Trust & Ors [2019] NZCA 532

By way of background, the Fisheries Act regulates commercial, recreational and customary fishing and its objective is to provide for utilisation of fisheries resources while ensuring sustainability. The Court of Appeal observed that while s 30(1)(ga) of the RMA is about maintaining indigenous biological diversity, the Fisheries Act is focused on the sustainable utilisation of fisheries. In its view, the two pieces of legislation complement each other; they both apply to the coastal marine area and allow decision makers to impose controls to protect biodiversity.

The Court of Appeal agreed with the lower Courts that any controls imposed under ss 30(1)(f)(i), (ii) or (vii) are explicitly subject to the Limitation, whereas the function of maintaining indigenous biological diversity in s 30(1)(ga) is not. However it disagreed with the High Court that regional councils can only exercise their functions around maintaining indigenous biological diversity when “strictly necessary”.

As set out above, BOPRC proposes to prohibit the removal, damage or destruction of any flora and fauna in the three protection areas around Motiti Island. The Court of Appeal observed that this prohibition amounts to controlling the taking of fisheries resources, and such controls would also engage s 30(1)(d)(i) (and possibly (ii) or (vii)). In that sense, the function of maintaining indigenous biological diversity can be subject to the Limitation.

This Limitation is aimed at managing fisheries resources to control their taking, allocation or enhancement. In determining whether a control implemented under ss 30(1)(f)(i), (ii) or (vii) will contravene the Limitation, the Court of Appeal noted that the following five indicia may provide some guidance:

- Necessity – whether the objective is already being met through measures implemented under the Fisheries Act;

- Type – controls that set catch limits or allocate fisheries resources among sectors or establish sustainability measures for fish stocks would likely amount to fisheries management;

- Scope – a control aimed at indigenous biodiversity is likely not to discriminate among form or species;

- Scale – the larger the scale the more likely the control is to amount to fisheries management;

- Location – the more specific the location and the more significant its biodiversity values, the less likely it is that a control will contravene the Limitation.

In summary, the effect of the Limitation is that regional councils can control fishing and fisheries resources provided they do not do so to manage those resources for Fisheries Act purposes.

The Court of Appeal agreed with the High Court that declarations were not appropriate, as the questions of law were separated from their factual setting and it would be very difficult to craft declarations which neatly encapsulated its reasons. The effect of this is that the reasons given throughout the decision will need to be interpreted to determine whether its conclusions apply in different circumstances.

It is likely that this decision will pave the way for more marine protection areas around New Zealand.