After much anticipation, the Government has now unveiled two of the three new replacements to the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA)

– the Spatial Planning Act (currently the Spatial Planning Bill) (SPA); and

– the Natural and Built Environment Act (currently the Natural and Built Environment Bill) (NBA)).

The third bill is the Climate Adaptation Act which will be introduced to Parliament at a later date and is expected to become law in 2024.

The NBA is the core piece of legislation and will work in tandem with the SPA as a single integrated system with shared definitions, outcomes, functions, and processes. We set out some of the key system changes below.

Natural and Built Environment Act

The NBA bill updates the RMA’s sustainable management purpose by replacing it with two limbs – the first is about the way that use, development and protection of the environment is enabled (including in a way that complies with environmental limits and targets), and the second is to recognise and uphold te Oranga o te Taiao. Te Oranga o te Taiao is a te ao Māori concept that is defined as:

- the health of the natural environment; and

- the essential relationship between the health of the natural environment and its capacity to sustain life; and

- the interconnectedness of all parts of the environment; and

- the intrinsic relationship between iwi and hapū and te Taia.

The lists of matters in ss 6 and 7 of the RMA are gone and replaced with a list of decision-making principles and system outcomes, which are intended to shift the focus from managing adverse effects to promoting positive outcomes. As there is no hierarchy between outcomes, this leaves decision-makers to determine how they are to be implemented and could lead to the familiar dilemma in how to balance competing priorities.

The avoid, remedy, mitigate direction has been replaced with a direction to avoid, minimise, remedy, offset, or provide redress, along with introducing an effects management framework in the legislation for some situations. The concept of “trivial” effects has also been introduced – adverse effects are defined to exclude trivial effects, and activities creating more than trivial adverse effects on specified nationally important places or highly vulnerable biodiversity areas can only be considered for approval if an exemption applies.

The NBA Bill elevates the importance of te Tiriti o Waitangi by replacing the “take into account” direction in the RMA with a “give effect to” direction.

It introduces a National Planning Framework (NPF), which will consolidate existing national direction, as well as some new functions. It is intended to provide directions on the integrated management of the environment, and will be rolled out in stages. The first stage will be to transition the policy intent of existing national direction (including the national policy statements for freshwater management and highly productive land), along with the medium density residential standards introduced in 2021. It will also introduce new content on infrastructure and natural hazards.

Regional planning committees will be established for each region to prepare a regional spatial strategy and a natural and built environment plan – reducing the number of plans from over 100 under the RMA to 15 under the NBA. These committees will have Māori and local authority representatives, along with central government representatives in relation to regional spatial strategies. Local authorities will still implement and administer the plans, which will have a similar function to regional policy statements and regional and district plans.

Local authorities will continue their role as consent authorities but the activity statuses have been reduced to permitted, controlled, discretionary and prohibited.

Spatial Planning Act

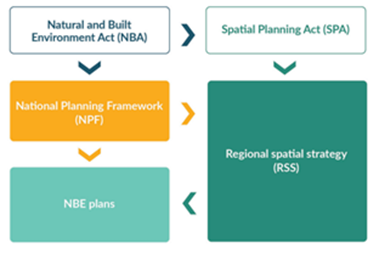

Regional spatial strategies will provide long-term, high level, and strategic direction for integrated spatial planning. The SPA provides for this mandatory spatial planning, along with promoting the integration of various pieces of legislation including the NBA, Local Government Act 2002 and the Land Transport Amendment Act 2003. The relationship between the NBA and SPA, along with their planning instruments, is shown as:

Transition

Many detailed transitional provisions have not been included in the bills but policy decisions have been made by the Government.

There will be an approximate ten year transition period until all new regional spatial strategies and natural and built environment plans are in force. During this period, new national direction under the RMA can continue to be developed, with a requirement to consider the desirability of consistency with the NBA. The RMA national direction will continue to direct RMA plans and policy statements, and transitional decision making – meaning that the freshwater planning process will continue.

However, during this period shorter-term consents will be issued for freshwater takes and discharges under the RMA, which will expire within three years of the relevant NBE plan being notified. There will be some exemptions to this, including for some renewable electricity generation activities.

Parts of the NBA will come on line at different times, to replace the RMA using a staged approach. A staged approach to planning is anticipated, with three regions going first to regional spatial plans followed by another group 12 months later, which will be followed by the development of natural and built environment plans. The RMA system will start dropping off as the new plans come on line. Some provisions will have immediate effect.

Next Steps

Once the House has debated the bills, it will decide if the bills should progress to the Select Committee stage and the public will then have an opportunity to make submissions. The Government aims to pass the bills before the end of this parliamentary term.

Please get in touch to learn more about the new bills and how it could affect you or your business.